Tucker Ellis: Kicking Off a Career in Marine Research

I am currently a rising senior at Tufts University studying biology and environmental studies. I hope to pursue graduate studies in marine biology, but I was introduced to this field a little differently than many other students and professors I’ve spoken to, who seem to have discovered marine science on a whim.

I grew up in central Maine (about a two hour drive from the Darling Marine Center!), and about 45 minutes away from the Gulf of Maine coastline, so the ocean has always been a core part of my life. Some of my fondest memories include sea kayaking trips, sliding down seaweed-covered rocks, and walking across intertidal zones with my parents searching for green grabs and periwinkles. Side note – though my family is not in the lobster industry, it’s safe to say we are responsible for the consumption of many lobsters from the Damariscotta River.

My father is a university professor with a background in atmospheric chemistry and interests in chemical oceanography and marine science in general. I grew up listening to him discussing ocean dynamics and climate change, and I remember reading excerpts from marine biology and chemistry textbooks on his shelves and thinking “what the hell are they talking about?” – actually, not much has changed in that regard. When my middle school teachers asked me about career aspirations, I thoughtlessly said I wanted to be a marine biologist – partially because I thought the ocean was mysterious and fascinating, but more so because I wanted to impress and emulate my father.

After graduating high school and preparing to start my first semester of college, more doubts started to arise. I began to ask myself: am I pursuing a career in marine science just to impress my father, or am I genuinely interested in it? Is marine science my passion or his passion? Frankly, the answers to these questions took a while to discover. Through my first couple of years of college, indecision about my major and my future plagued me until I finally found the missing piece – hands-on research. I first spent five months researching green crab and zebrafish physiology. Then, I was awarded a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) at Texas A&M University, where I studied ctenophore population density and environmental conditions in Galveston Bay as a function of anthropogenic climate change. I learned that I loved field work, the camaraderie of a research team, the flexible schedule, and I could even tolerate programming.

Fast forward about a year, and here I am back in Maine at the Darling Marine Center (DMC). My other interests have not disappeared, but marine science has risen to the surface (no pun intended), and I no longer feel dishonest while I do my research. I’m currently interested in the intersections between marine biology and climate science: the physiological responses of marine organisms to climate change, and the role these processes play in species range shifts and population dynamics, with a focus on phytoplankton and zooplankton.

After considering a few summer internships in different locations, I was especially drawn to the DMC. Having spent the last two summers in Virginia, West Virginia, and Texas, I had been missing the beautiful Gulf of Maine and was eager to do research in a place that felt like home; I wanted to, once again, experience the sense of familiarity and small-town community that makes Maine such a special place. Additionally, I found that the DMC’s mission statement aligns well with my goals of conducting novel, interdisciplinary research that connects undergraduate researchers and scientists with aquaculture industry members and local policymakers.

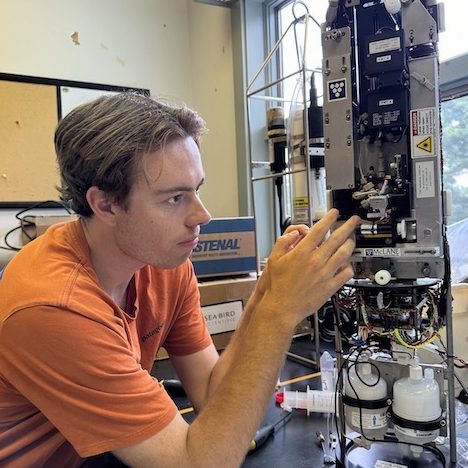

This summer, I’m an intern in the Brady Lab using the Imaging Flow Cytobot (IFCB) – an autonomous robot that uses flow cytometry and laser technology to capture high-resolution, real-time images of particles in water samples – polymerase chain reactions and enzyme immunoassays to explore the community structure and dynamics of phytoplankton in the Damariscotta River and to quantify the toxin levels of observed harmful algal blooms (HABs). I’m particularly interested in this line of research because of the ecological and economic importance of the Damariscotta River, and the opportunity to potentially inform governmental decisions regarding the shellfish industry. For reference, the river is home to one of the largest shellfish industries in the northeastern United States, having yielded $11 million in revenue in 2023. In the past, HABs dominated by the neurotoxin-producing diatom Pseudo-nitzschia australis have been observed in the Damariscotta River and across the northeastern United States, which have led to the temporary closures of shellfish areas and a loss of revenue. Despite the importance of this river, its phytoplankton community dynamics have been minimally studied to this point, especially at short-term temporal scales.

So, this research presents a unique opportunity to study the phytoplankton community structure and dynamics in the Damariscotta River, which may help to identify the presence of toxin-producing species and inform governmental closures of local shellfish areas.

I’m not exactly sure what my plans are for graduate school (thankfully I still have a few months to figure that out!), but I hope to stay on the water and continue studying phytoplankton and zooplankton, or as one of my friends described them, “the tiniest, most boring things in the ocean.”